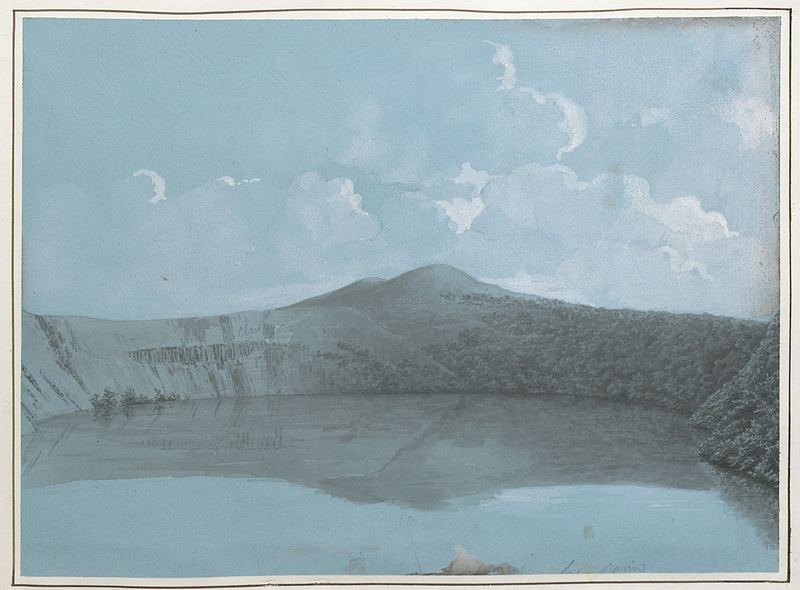

In olden times…dark legends shrouded Lake Pavin like a mournful veil: vanished men, plaintive voices heard at night beneath the waters, terrifying monsters, supernatural apparitions…

-from Herborisations à La Bourboule et au Mont-Dore (1887) by Francisque Morel

Years ago, I introduced the idea — for the first time — that Auvergne is the “Transylvania of France”. Since then, I’ve explained my reasoning in several articles and performances, with the aim of throwing light on the dark corners of Auvergne’s occult geography. Starting from at least as early as the medieval era, chroniclers portrayed the region as a shadowland of spectres and werewolves, and throughout my work I’ve sought to popularise this heritage by drawing attention to haunting landmarks. As I see it, the most tangibly haunting — and haunted — of these sites is Lake Pavin (or Lac Pavin).

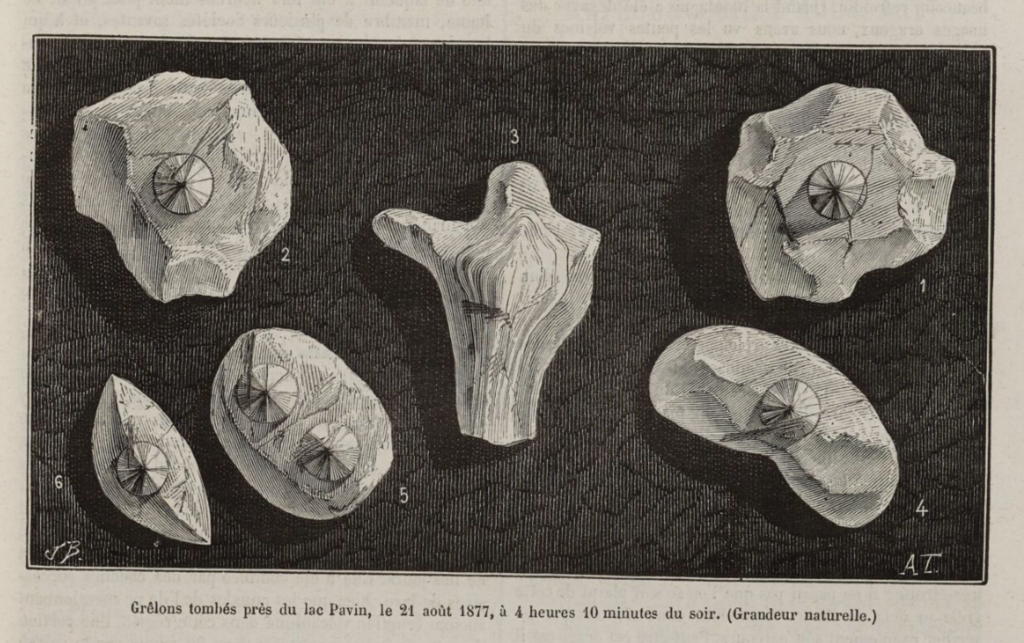

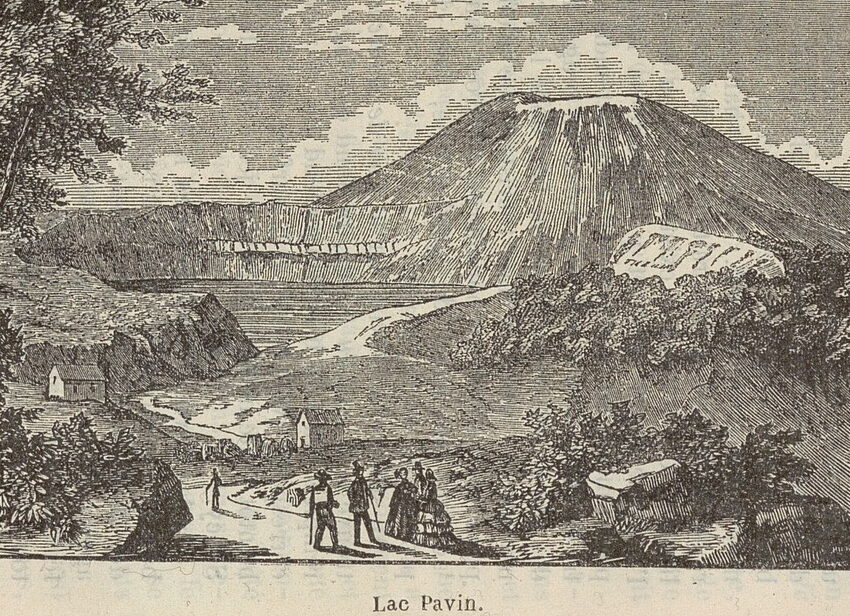

If there were demons or some kind of undiscovered plesiosaurian cryptid in Auvergne, Pavin is where you would find them. Described since at least the 1560s as a lake that raises — at will — tempests of thunderbolts and hail, Pavin occupies the crater of an ancient volcano near the highland town of Besse-et-Saint-Anastaise. In addition to being Auvergne’s deepest lake (the Flatiron Building in New York City could easily fit inside it), Pavin could also be seen as the most haunted lake in France. It deserves this title precisely because it is actually haunted.

Irrespective of what one might believe about the existence of goblins, ghouls, and lake monsters, Pavin’s geographical location as well as its chemical components make it a place where strange things — from flash hailstorms to tornado-like waterspouts — can be seen. Like some African lakes (Nyos and Kivu, for example) Pavin contains high concentrations of gases like carbon dioxide. This fact makes the lake particularly susceptible to limnic eruptions, which are where large amounts of carbon dioxide get displaced and burst through the surface, triggering phenomena reminiscent of the Biblical plagues.

Although evidence suggests that a number of people have witnessed eruptions and extreme meteorological events over the centuries, written testimonies are hard to come by. However, the following account from the eighteenth-century newspaper Le Moniteur Universel is a vivid illustration of why locals reputedly avoided the lake before the advent of the modern era. My friend, Michel Meybeck (the first modern writer to attempt a scholarly analysis of Pavin’s geomythology), first alerted me to the passage, which is referenced in his 2019 article, “La Longue et Terrible Histoire des Lacs-Maars”. I’ve included my translation below:

Most craters have been completely hollowed out by their final eruptions and still retain, to varying degrees, the shape of an inverted cone. The Puy de Pariou is a stunning example of nature’s work, unmatched by any known active volcanoes. Some of these deep cavities are now filled with water, forming high-altitude lakes fed only by underground springs. The most striking is Lake Pavin, nestled on the steep slopes of Mont-Dore, surrounded by a sheer, 26-metre (80-foot) rim carved from ancient lava flows. You’ll find the following account of a phenomenon observed there in August 1785 by Legrand and Enjelvin, as told to me by the latter, quite fascinating.

Drawn to these heights for the same reasons as us, and exhausted from intense heat, they rested on the steep cliffs overlooking the lake. Their eyes, initially scanning the distant mountains, were soon drawn to the lake by a sudden, low rumble. A thick cloud had formed over the centre of the bubbling water, spinning rapidly. Within moments, the wind grew fierce, the vapours thickened excessively, and a waterspout, 6 metres (18 feet) wide, began rising straight into the air. As soon as it cleared the crater’s edge, it stopped ascending and instead released a dense fog that swiftly enveloped the mountain and its surroundings. Fuelled by the waterspout’s rapid motion, this stormy cloud swirled in place for a long time before collapsing back into the crater. Around this time, a deafening thunderclap echoed for fifteen minutes, accompanied by blinding lightning flashes in quick succession. Gradually, the thunder faded, the cloud thinned, and it eventually vanished entirely. After two hours, the air was calm again, the strange event over. When the travellers descended to the crater’s base, they found a layer of fine hail, 20 centimetres (7 inches) thick, blanketing the lake’s narrow shores.

Obviously, this isn’t the sort of thing one would expect to see at Pavin every day. Weather spirits — even Vulcan himself — evidently take days off like the rest of us. That shouldn’t stop people from making the trip. The lake, which is about an hour’s drive from Clermont-Ferrand, is surrounded by acres of picturesque woodlands, making it the ideal destination for picnics, nature walks, and the odd moonlight stroll. Swimming, of course, is forbidden. The most haunted lake in France — and the Dwellers that rule its abyss — are not to be trifled with.

In the words of the American folklorist Charles G. Leland: “Minor local legends sink more deeply into the soul than greater histories.” To learn more about Auvergne’s seemingly endless secrets, sign up for our newsletter below.