In Maurice Leblanc’s The Hollow Needle, the legendary Arsène Lupin claims association with a Clermont-Ferrand criminal who was — at the time — probably the most infamous gentleman thief in France. “Do you remember,” he asks the young detective Isidore Beautrelet, “Thomas and his gang of church pillagers in the South — agents of mine, by the way?” Although Lupin makes no mention of Clermont-Ferrand, all of Leblanc’s Belle Époque-era readers knew exactly what he was talking about.

In autumn 1907, two years before the publication of The Hollow Needle, newspapers churned out reports that police had located the headquarters of an international syndicate of thieves in Clermont-Ferrand. The head of this organisation, their catchy write-ups explained, was a thirty-something-year-old barrel-maker named Antony Thomas. The media followed Thomas’s trial for months, publishing juicy details on how he, with the backing of a powerful network of British and French art dealers, clandestinely masterminded the looting of churches across France.

Reports also emerged of Thomas’s extensive library, which included detective novels, histories of famous criminal trials, and catalogues of medieval art. By December, much of the Western world had read of his exploits. Yet, today, only a few are acquainted with the story of how the Arsène Lupin of Clermont-Ferrand created “the biggest sensation France has experienced in years”.

Thomas first got his start in the thievery business a year before the passing of the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and State. At the time, government officials were drawing up inventories of church treasures. These lists, which described the sizeable wealth of many Catholic properties, apparently came to the attention of networks of antiquities traders in London, Clermont-Ferrand, Paris, and Lyon. Thomas was well-connected, and his employers likely knew that large amounts of stolen goods could be hidden in his factories and workshops across Clermont.

Initially, Thomas’s role was not as a thief, but as a buyer. Guided by antiquary contacts who were working fast to fill orders from collectors overseas, Thomas made silver-tongued proposals to local priests and rectors, reminding them of the financial losses and confiscations they were likely to suffer once France became a secular nation. Always the gentleman, he promised to stop this unglorified and uncompensated spoliation by purchasing each church’s valuables and replacing them with cheaper lookalikes. Ordinary parishioners, he reassured the clergymen, would never notice the difference between the real artefacts and his counterfeits.

Several of his targets apparently agreed to the deal, and this was how Thomas made his first earnings. His method was simple but effective. Prior to each sale, Thomas’s Paris team would provide him with an unregistered car along with the art replica. Afterwards, he would pay the priest, exchange the objects, and bring the original to the Parisian dealers at an agreed checkpoint. The item would then be smuggled to Paris or Marseille before being shipped off to buyers in Berlin, London, New York, and other cities.

This secret trading of church rarities continued until wealthy collectors started asking Thomas’s patrons in Paris to recover intricately designed items that could not be easily or compellingly reproduced. Aware that country churches were “guarded in a most temptingly inadequate manner”, Thomas rose to the occasion. In December 1904, he and an accomplice, Antoine Faure, stole a fourteenth-century Madonna statuette from the Notre-Dame de Sauvetat, a church situated near the Puy-de-Dôme city of Issoire. Emboldened by his first swindle, Thomas spent the next few years until his arrest in October 1907 developing what The New York Tribune described as “a syndicate of gentlemen burglars”. Guileful and well-informed, they moved invisibly in the shadows, pilfering a flurry of rural churches in Corrèze, Haute-Vienne, Haute-Loire, Puy-de-Dôme, and other departments.

When they were on a job, Thomas’s crew, which included men and women, posed as bumbling tourists. While they distracted the — often elderly — church caretakers, Thomas slipped past them, snatched the spoils, and sneaked away. Sometimes, however, Thomas acted alone. In May 1907 for instance, Thomas drove from Clermont-Ferrand to Saint-Nectaire in order to go after the gem-encrusted reliquary bust of St. Baudime. Once inside, he spent some time wandering through its aisles while rifling through a guidebook. When the coast was clear, Thomas snatched the statue, replacing it with a papier-mâché copy. Afterwards, he calmly walked to his car and sped away.

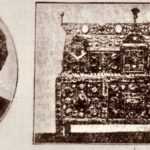

For a while it seemed that Thomas & Co. — as they were later dubbed in the media — would never be brought to justice. But all this changed after the gang’s heist of the Chasse of Ambazac, a dazzling enamelled chest. A letter, likely penned by one of Thomas’s underworld enemies, tipped off police to an alleyway in Clermont-Ferrand’s Ballainvilliers quarter. In tunnels located beneath an unassuming house, detectives found the St. Baudime reliquary, statues, crosses, embroideries, and a treasure-trove of other stolen loot. Police also discovered surgical instruments, client lists, vials of poison, and a cache of illegal weapons.

Suspicion soon fell on Thomas, who had frequently been seen drinking at the premises with groups of friends. After police arrested Thomas’s mother and brother, Thomas turned himself in. During his trial, the Clermont Lupin claimed that his rich benefactors had conspired against him. Vengeful, he sang like a canary, implicating a number of art dealers in Paris and Clermont-Ferrand.

In March 1908, he was sentenced to six years’ penal labour while his wealthier associates, such as the antiquaries Michel Dufay and Charles Tricou, got off scot-free. Without him, Thomas & Co. — once one the most effective criminal enterprises in Europe — crumbled. Although they eventually recovered the Chasse of Ambazac, investigators never managed to find everything. Thomas claimed that much of what he had stolen ended up in the hands of American elites. Perhaps, if the fates allow, these long-lost church treasures, the remaining fruits of the labours of a real-life Lupin, will turn up again one day.

To receive more information on Hidden Clermont-Ferrand — sign up for our newsletter below!