“It was out of the ‘bottomless’ Lac Pavin that the sorcerers conjured wind and storm by casting a stone into its enchanted waters…”

-Margaret Roberts

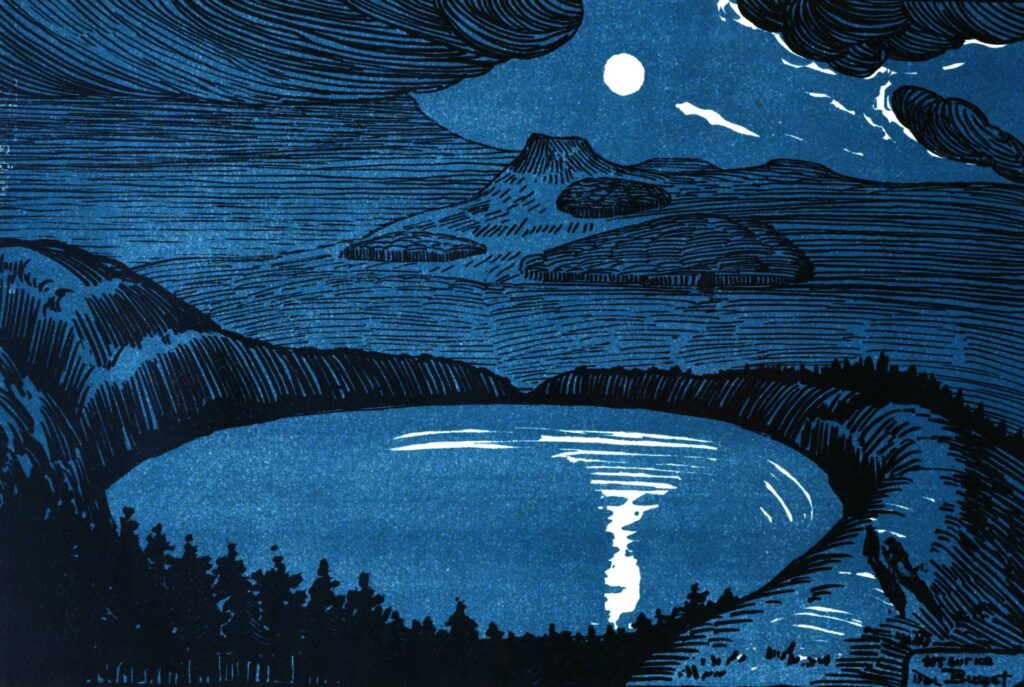

Situated inside a volcanic crater in the Dore Mountains, Lake Pavin is the deepest lake in Auvergne. Its entrancing appearance, which has been a subject of interest for travel writers and geographers for the past four hundred years, has all the hallmarks of an elfin scene from a chivalric romance. Undines seem to hide beneath its glittering, motionless surface, and goblins (especially in the moonlight) seem to haunt the forest of fir trees that lines its banks.

And so it should come as no surprise to find that for years, Pavin’s depths were thought to be fathomless, the abysmal abode of dragons, spirits, and even the Devil himself. Some of these tales date back to the Renaissance, others — such as the story that ruined city rests on the bottom of the lake — have more recent origins. Yet nearly all of Pavin’s legends say that the lake hides infernal forces, forces that — from time to time — bubble up to the surface and disrupt the weather.

One of the earliest accounts of Pavin’s strange geological and meteorological activity comes from Paul Merula’s Cosmographia (1614). Although he did not mention Pavin by name, Merula described a lake near “Besse in Auvergne” which produces hail, lightning, and rain whenever a stone is thrown into it. Merula’s description is also similar to a passage in Francois Belleforest’s supplemented translation of Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia (1575). In the work, Belleforest wrote that a “terrifying” and volatile lake can be found in the vicinity of Besse near “Mount Dore”.

According to folklorist Paul Sébillot, these stories about a dangerous mountain were inspired by a report from Gervais of Tilbury, a thirteenth-century historian. In his Otia Imperiala, Tilbury mentioned a demon-infested, tempest-raising lake on the summit of an inaccessible mountain in Catalonia. Like Pavin, this lake had an “inscrutable” depth and did not take kindly to projectiles that landed on its surface.

More variants of the stone-throwing trope also appear in folk stories about other European lakes, such as the Mummelsee. Yet some have argued that features of Pavin’s mythology were derived from amateur observations of the lake’s seismicity. In fact, according to Michel Meybeck, an emeritus professor and geologist at the University of Paris VI, Pavin’s legends have more than a grain of truth in them. In Meybeck’s view, Pavin’s legends are useful tools for understanding how pre-modern peoples might have interpreted geological anomalies.

In a 2017 study, Meybeck collated his lifelong interests in Pavin and his scientific research on maar lakes and limnic eruptions. Referencing the work of Thierry del Rosso, Pierre Lavina, Emmanuel Chapron and others, Meybeck argued that “degassing” events in the lake had a hand in shaping and perpetuating Pavin’s folklore. Meybeck’s theory is fairly straightforward. Pavin is meromictic, which means that it has layers of water that rarely mix. The bottom layer, which is rich in carbon dioxide, sometimes ejects gas into the atmosphere when the lake bed is disturbed by intense seismic activity or sudden landslides.

To support his thesis, Meybeck provided evidence for two major sedimentary shifts in Pavin which took place in the seventh and fourteenth centuries. He also cited witness descriptions of an eruption which occurred at lake Nyos (a similarly gas-saturated maar) in Cameroon in 1986. The Nyos event caused mass casualties and produced rare, Biblical-like phenomena, such as brief lightning strikes, gurgling waves, thunderclaps, clouds of toxic vapour, and rising columns of water. All these effects were triggered by a tremor that caused the lake’s overabundance of carbon dioxide to violently rise to the surface. These facts, Meybeck surmised, show that Pavin could have generated similar spectacles during its two prominent sediment slumps.

As for the stone-throwing trope, Meybeck has proposed two possibilities: the trope is either a metaphor for rock slides or an exaggeration of a real phenomenon. Fascinatingly, Meybeck believes the seemingly impossible reality that stones and other debris could have set off detonations at key moments in Pavin’s history. The main evidence in support of this idea is data from Cameroon’s highly concentrated Monoun lake, which can reportedly produce minor explosions on the surface when triggered by splashing or other small movements.

Meybeck’s findings — while impressive and thought-provoking — are still open to debate. Nevertheless, he has succeeded in recovering and popularising Pavin’s unique, centuries-old geomythology. Without a doubt, Pavin, which has long captured the imagination of Auvergne’s inhabitants, will continue to inspire further enquiries into its mysteries.

An earlier version of this article was originally published in The Thinker’s Garden — a sister publication of Visit Auvergne.