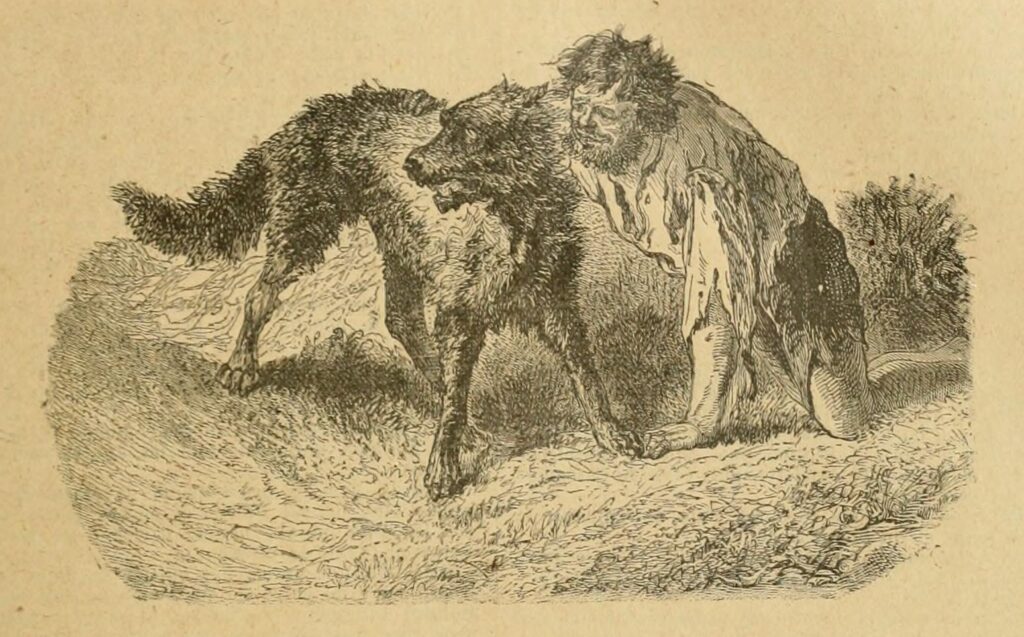

“At the end of the last century, especially in the countryside of central France, people still believed in the werewolf — a mysterious creature of unparalleled wickedness, whose exploits were told and feared even by the ancients.”

– from “Plesiosaures et Loups-Garous” (1922) by Paul-Louis Hervier

If you were living in Puy-de-Dôme 150 years ago, chances are that you or one of your close friends or family would have encountered at least one werewolf at some point. Although it may be hard to imagine now, the Auvergne of yesteryear was a world entirely unlike the present. To many Auvergnats, werewolves were not make-believe monsters to be mentioned in passing with a smile and a wink; they were tangible, criminally-inclined human beings who possessed — by Satanic favour — powers that far exceeded those of ordinary mortals. Always outcasts, werewolves were gossiped about by day and feared by night. Villages sometimes even had their own designated “werewolf family”, a group of “undesirables” who were shunned because of their ethnic origins, moral peccadilloes, or behavioural eccentricities.

To illustrate what a “community werewolf dynamic” — if we can call it that — could have looked like in nineteenth-century Puy-de-Dôme, I’ve included an excerpt from Voyage en Auvergne by Louis Nadeau. Published in 1862, the book is a kind of travel memoir that outlines Nadeau’s firsthand experiences with the folkways and geography of Auvergne. In the text below, a local man from Orcines tells Nadeau about the role and reputation of werewolves in his village.

Mass [in Orcines] has come to an end. Upon two barrels supporting a few planks, the musicians begin their revelry…A few steps away, in a meadow, both middle-aged and old men are playing bowls. A sort of calm majesty presides over their movements. I see some who display great skill, and everyone applauds. People form a circle around them.

I stand beside a spectator who is no longer youthful, yet not old either. He has an intelligent look. His hair is cropped short in front and long in the back. His knife is fastened to his belt by a double copper chain. I address him. He looks at me with suspicion; his brow darkens, his lips tighten, he hesitates. But, seeing the gentleness and consideration with which I put my questions, he gradually grows more at ease and even becomes quite talkative. A group — a father, a mother, a young girl of twenty, and three younger children — stood apart, separated from all the other peasants, watching from afar without daring to join in the game. I ask my neighbor whether these people had any reason for keeping so much to themselves.

“Yes, sir,” he replied. “Those are the wretches who have disgraced the honour of the village.”

“How so?”

“That tall girl you see among them made a mistake — and that mistake has not been amended. She will probably be forced to leave the district. Her lover, who already no longer dares show himself, will do the same. It is he who refuses the marriage. We never tolerate any offence against morality here.”

“But the parents are not guilty, surely?”

“Oh yes, sir. If they had watched over their daughter properly, this would never have happened. They too will have to leave. They must bear the penalty for their negligence.”

There was nothing to reply to that severe logic of mountain morality.

“You see,” he went on, “that other group sitting far from the dancers? It’s made up of a man, a woman, and two small children. Well, they never join in our amusements — we would not allow it.”

“What crime have they committed, then?”

“None. They are sorcerers.”

“Ah!”

“Yes, sir.”

“And what proof do you have of that?”

“What proof? Why, first of all, their grandfather owned absolutely nothing, and today they are the richest people in the village. Only through a pact with the Devil could they have grown rich so quickly.”

There was nothing to be said to that.

“Next,” he continued, “that man you see sitting there beside his wife has been caught several times in different animal forms.”

“Really?”

“Yes, sir. Grand-Pierre— there he is — was one evening returning to the village. He heard footsteps behind him; he turned and saw himself followed by an enormous wolf that began making prodigious leaps and seemed ready to devour him. But Grand-Pierre is strong and not easily frightened; he stopped, raised his staff, and struck the wolf across the loins while seizing its head with his left hand at the very moment it leapt. Imagine his astonishment — he recognised that man there, who begged him not to hurt him. Big Peter is not cruel; he let the fellow go, but he told the whole village what had happened.”

“Had Grand-Pierre ever quarrelled with the sorcerer before?”

“Oh yes; some time before they had appeared before the justice of the peace over a disputed field.”

“I see.”

“Since that time, many others have seen him — some in the form of a dog, others as a goat. It seems he runs about every night. For my part, I have never met him; but I well remember that his brother, the roofer — who no longer lives here — was also a sorcerer. It was said that the Devil himself supported him on the steepest rooftops when he climbed them in dreadful weather.

“One day he was working on that slate roof you can see from here. Suddenly Jean-Guillaume, who was talking with us, cried out: ‘Look at Pierre Migat dancing on his roof!’ We looked. I saw nothing, but the others swore they had seen him leap horizontally through the air and come back down upon the roof like the ball a child throws to the end of a string and then pulls quickly back again. They say that amusement went on for quite a while. And since no one wanted to speak to him any longer, he left and went off to make his fortune elsewhere.”

In the words of the American folklorist Charles G. Leland: “Minor local legends sink more deeply into the soul than greater histories.” To learn more about Clermont-Ferrand’s seemingly endless secrets and ghostlore, sign up for our newsletter below.